|

Modified by PolGeoNow from map included in public court documents (original created by International Mapping).

|

Latest World Court Ruling: Nicaragua v. Colombia Sea Dispute

Judgments handed down by the UN's International Court of Justice (ICJ) - also known by semi-official nickname "the World Court" - can be pretty interesting to political geography nerds like us. Often they establish new land and sea borders or end long-running territorial disputes, as you might have seen in our past coverage of the Burkina Faso/Niger, Peru v. Chile, Costa Rica v. Nicaragua, and Somalia v. Kenya cases.

On the other hand, there are plenty of ICJ cases that have nothing to do with drawing lines on a map, and you could be excused for assuming that the Nicaragua v. Colombia judgment from this past April was one of those. After all, it was mainly about Nicaragua's accusations that Colombia simply wasn't respecting a sea border already drawn by the court in 2012, which theoretically ended a dispute around several Colombia-claimed islands in the Caribbean Sea near Nicaragua.

But as it turns out, there actually were some map-changing outcomes from the April judgment: Besides deciding that Colombia had indeed acted illegally in Nicaraguan waters in several cases and had to stop, the court also ruled on some territory-related claims by both Colombia and Nicaragua, establishing the legal status of lines on the map that had previously been disputed.

Colombia's "Integral Contiguous Zone"

The first topic of interest in the judgment is Colombia's "Integral Contiguous Zone", which it claimed gave it the rights to conduct various law enforcement maneuvers around and between its Caribbean islands, even on Nicaragua's side of the border the court drew in 2012. Colombia seems to have invented the term "Integral Contiguous Zone", though a normal "contiguous zone" was already a thing in international law:

The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) establishes that beyond a country's "territorial sea" - a strip of water up to 12 nautical miles (NM) wide that counts as fully part of the country - there can also be a "contiguous zone" where the country can run "customs, fiscal, immigration or sanitary" law enforcement operations (though it can only do that in cases that are relevant to violations within the 12-mile territorial sea).

Nicaragua came to the court complaining that Colombia's contiguous zone was set up illegally,* and the judges ended up agreeing, on two different counts:

First, the UNCLOS states that the contiguous zone can't go more than 24 NM beyond the country's "baselines" (basically its coast, but see later in this article). And instead of just defining lines 24 miles from each one of its islands, Colombia had gone farther and drawn one big outline to contain all those 24-mile circles and the gaps between them (this is apparently what it meant by "integral"). The result was that, in the larger gaps between islands, Colombia claimed waters as part of its contiguous zone that weren't actually within 24 NM of any land.

|

Modified by PolGeoNow from map included in public court documents and created by International Mapping.

|

Second, the Colombian law establishing the contiguous zone asserted that patrols could use the zone to protect Colombia's "security", including actions against drug smuggling, piracy, and environmental damage. However reasonable that might sound, the court couldn't find any basis in international law to allow those uses of the contiguous zone, except when related to enforcing customs and immigration rules for boats headed to or from the islands or their territorial seas.

More importantly, the power to enforce environmental protection laws is specifically a feature not of contiguous zones, but of "exclusive economic zones" (EEZs), which stretch from the territorial sea out to as much as 200 NM from a country's coastline. This wasn't really an issue where Colombia's contiguous zone overlapped with its own EEZ, but the thing was, big parts actually overlapped with Nicaragua's EEZ instead.

The court did make clear that there was no reason, in principle, that one country's contiguous zone can't overlap with another country's EEZ. But that crucially depends on the assumption that the contiguous zone and the EEZ each involve separate and mutually-exclusive powers - one country's customs checks on boats about to enter its territorial waters doesn't have to interfere with another country's right to regulate environmental protection, fishing, or oil drilling at the same location.

So in the end, the court came to these three conclusions:

- Colombia's "Integral Contiguous Zone" isn't legally valid anywhere that isn't within 24 NM of land

- Colombia can't claim environmental protection or other "security" powers within its contiguous zone (with some exceptions in areas that are also part of its EEZ)

- Colombia has to change its law to avoid claiming either the contiguous zone in the gaps beyond 24 NM or the extended powers anywhere they overlap with Nicaragua's EEZ

What about the parts of the "Integral Contiguous Zone" beyond 24 NM but within Colombia's own EEZ? The court did making a binding ruling that they were legally invalid, but didn't demand that Colombia do anything about it. Since the case had been brought by Nicaragua, the judges said they only had the power to give orders where Nicaragua's own rights were being directly violated.

*Colombia technically isn't directly bound by the UNCLOS, since its legislature never "ratified" the treaty (incorporated it into Colombian law). But its government agrees that it's still accountable to "customary international law" - the standard principles in practice by the world's countries - and in this situation those principles are considered to be based closely on the UNCLOS.

|

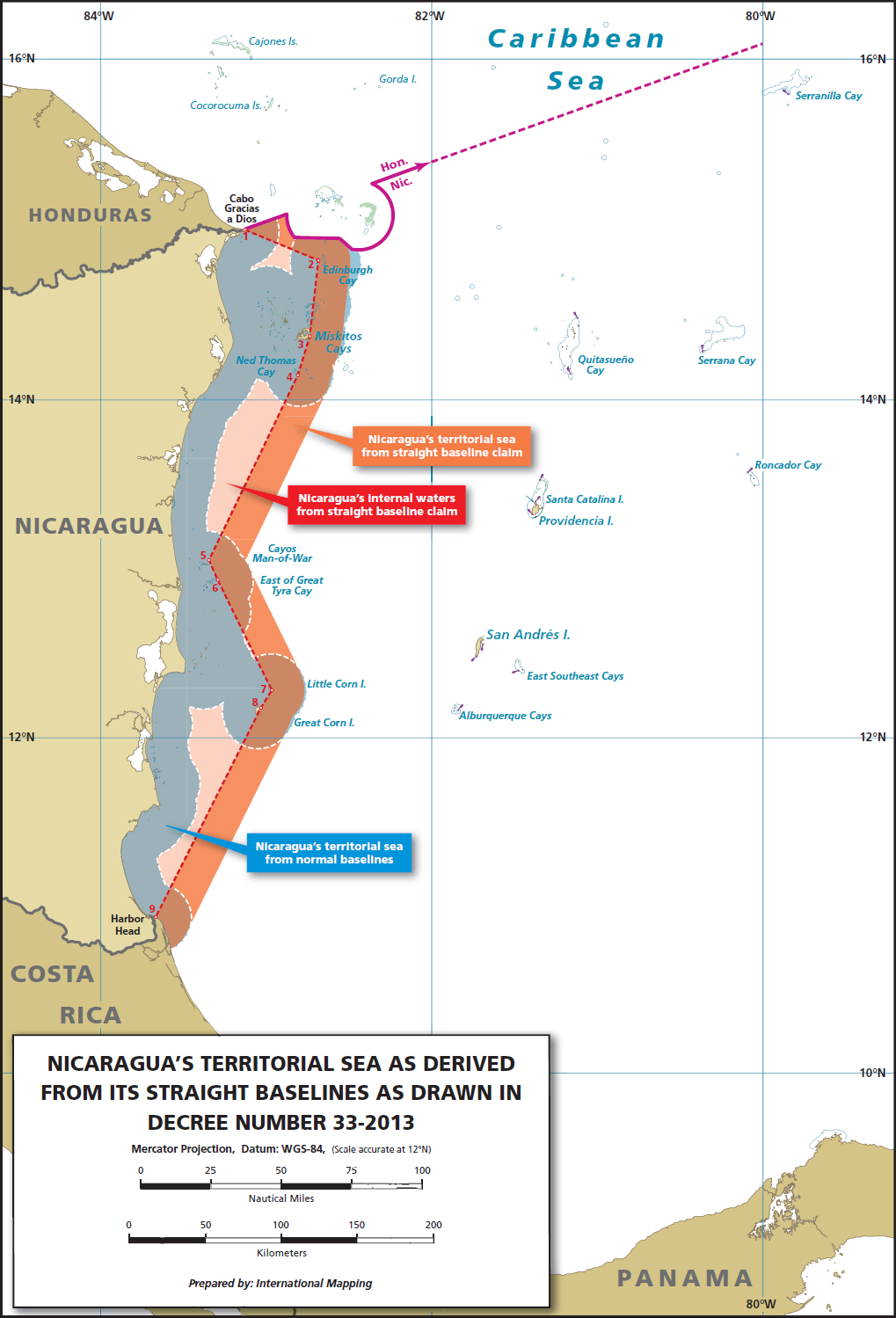

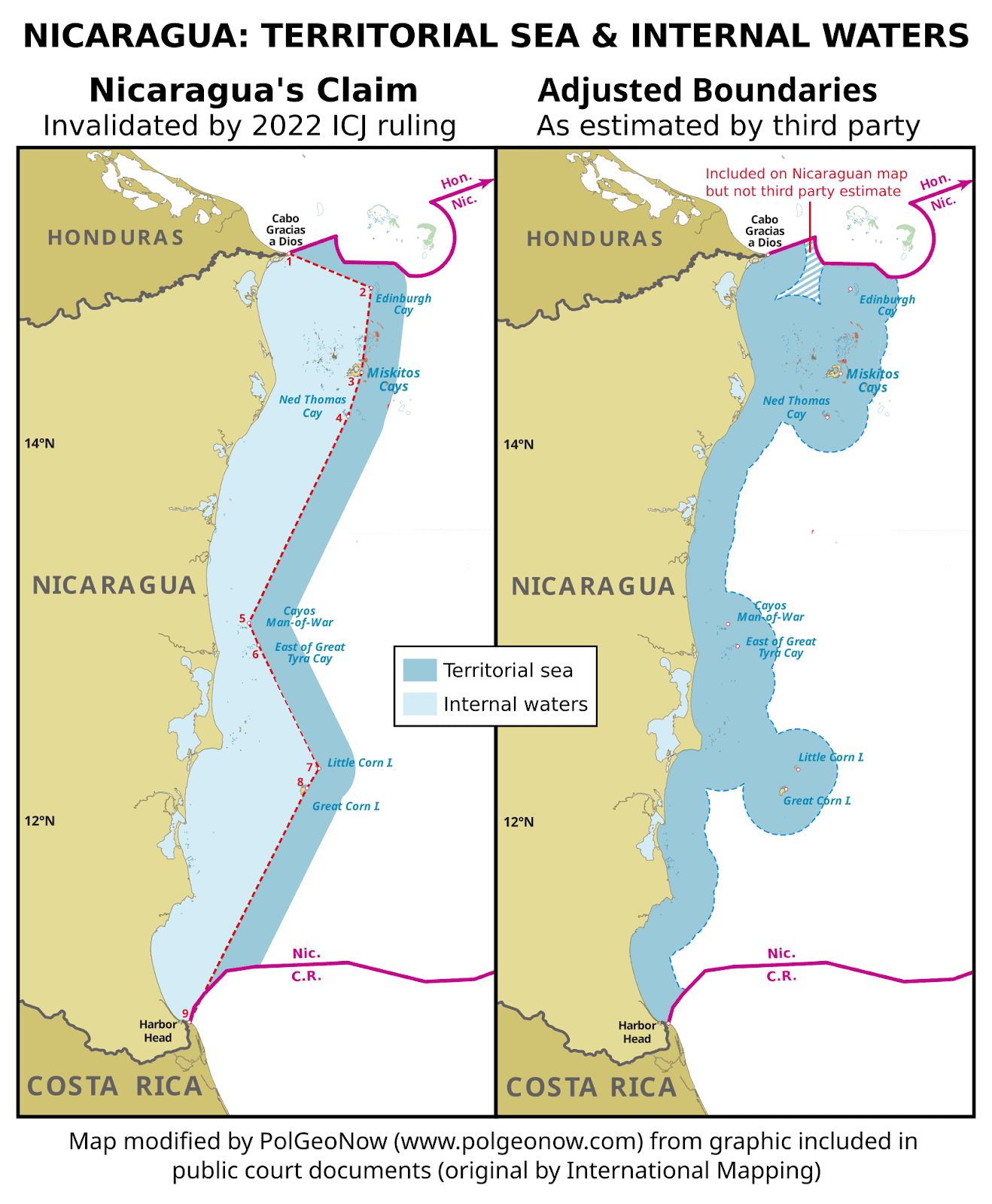

Map of Nicaragua's territorial sea and internal waters with and without straight baselines. Graphic from public court documents, created by International Mapping. See below for map with the two versions side-by-side instead of overlapping.

|

Nicaragua's Straight Baselines

Though the case was brought against Colombia by Nicaragua, that didn't stop Colombia from hitting back at what it said were Nicaragua's own violations of the Law of the Sea. In particular, Nicaragua uses something called "straight baselines" to define the starting point that its 12-mile territorial sea and 200-mile EEZ are measured from. Instead of measuring directly from its coastline, it draws a straight line connecting the dots between a bunch of different small islands just off the coast, and measures starting from there.

The result is that Nicaragua's claimed territorial sea, and potentially the EEZ, both stretch farther out into the ocean in some places than if it had measured them directly from the coast.* Not only that, but Nicaragua can also then claim a sizeable strip of sea between the islands and the mainland as "internal waters", where exceptions to a country's territorial sea powers - like a requirement to let foreign ships transit through - don't apply.

This "straight baselines" method might sound awfully similar to the principle behind Colombia's "Integral Contiguous Zone", and in a way is. But the difference is that straight baselines are well-established as legitimate according to the Law of the Sea - in certain cases. The idea is that countries whose coastlines are almost closed off by rows of nearby islands shouldn't have to treat the in-between waters any differently than they would treat a harbor or a lake. And if the islands really enclose the coast, drawing straight baselines doesn't make much difference in how far out the territorial sea or EEZ stretch anyway, because without them the 12 NM and 200 NM would still be measured from the coasts of those islands.

The problem, according to Colombia, was that it's really a stretch to say Nicaragua's Caribbean coastline is enclosed by a row of islands - that it's more like some clusters of islands here and there. And the court ended up agreeing that the straight baselines were invalid, despite Nicaragua claiming that they were justified by parts of the ICJ's own 2012 judgement. Not only that, but the judges said Nicaragua failed to prove that all the dots it was connecting were even legally real islands, as opposed to reefs that only stick out of water at low tide. The result was that large chunks of ocean between the islands had been claimed as Nicaraguan internal waters despite being wide open to the outer sea, and large chunks of ocean beyond them claimed as Nicaraguan territorial waters despite being more than 12 NM from any land.

Since, again, this was specifically a court case brought by Nicaragua against Colombia, the judges didn't feel they had the power to demand that Nicaragua change its law and withdraw the straight baseline claim. But they did rule that Nicaragua's specific straight baseline claim wasn't legally valid, implying that another country (such as Colombia), would immediately be justified if its ships ignore Nicaraguan claims to those extra territorial seas and internal waters. (In fact, Costa Rica and the US have also both disputed Nicaragua's use of straight baselines.)

*The effect of straight baselines on the EEZ is more subtle and less consistent than their effect on the territorial sea - at 200 NM out, one or

another of the coastal islands themselves is often just as close

as any part of the straight baseline.

|

Will Colombia and Nicaragua Accept the ICJ's Judgment?

The

short answer is "Apparently, yes". The International Court of Justice

insists that its judgments are legally binding, though it can be

difficult to enforce them if a country's government resists, as Kenya

has done since the judgment on its sea border dispute with Somalia

last year. In theory, the UN Security Council could authorize sanctions

or even a military intervention to force compliance, but in most cases

the countries' governments comply on their own, either voluntarily or

based on orders from their own courts, with the Security Council rarely getting involved either way.

And it looks like Nicaragua and Colombia have both more or less accepted this ruling. The Nicaraguan government, for its part, has enthusiastically welcomed the judgment as a whole, even promising to revise its baselines law to comply with the court's findings, despite the court not having directly ordered it to do that. Colombia's government has taken a different route, playing down the results of the case by spinning the overall judgment as a victory and barely mentioning the rulings against it.

Specifically, in press statements, Colombia's representatives mostly emphasized a list of things the court didn't tell Colombia not to do (some of which, based on our non-expert reading of the court documents, still sound like quite a stretch). But a Colombian newspaper article based on those statements still acknowledges that the government "will have to adjust" the contiguous zone, while in another report a Colombian representative said that a "special procedure" would be needed to implement the changes - seeming to imply that the government at least accepts its obligations in principle.

Meanwhile, when Nicaraguan leader Daniel Ortega publicly accused Colombia of refusing to recognize the judgment, Colombia's president didn't directly address the issue, but dismissed Ortega's claims as the words of a "post-truth" dictator.

But didn't Colombia reject the ICJ's jurisdiction in 2012?

On November 27, 2012, the week after the ICJ's first judgment setting the boundary between Nicaraguan and Colombian waters, Colombia's government moved to reject the court's ability to make judgments affecting the country. To do this, it announced it was withdrawing from the Pact of Bogotá, a treaty named after Colombia's own capital city, which made it clear that the ICJ had the authority to resolve disputes between most countries of the Americas.

That might make it sound like Colombia was refusing to accept the the 2012 judgment, but its government has stressed that its withdrawal from the pact wasn't retroactive, and only applied to future international lawsuits, meaning that it still had to accept the results of that judgment. And in fact, since the Pact of Bogotá specified that it takes a country one year to withdraw from it, Colombia was officially still part of the treaty until November 27, 2013.

The second ICJ case between Nicaragua and Colombia - the subject of this article - was first filed by Nicaragua on November 26, 2013 - the last full day before Colombia officially left the treaty. Though Colombia tried at first to argue that new ICJ cases couldn't be submitted against it during that one-year waiting period, the 16 judges of the court voted unanimously in 2016 to reject that argument, concluding that Colombia was stretching its interpretation of the rules too far and Nicaragua had gotten its application in just in time.

Colombia's Non-Implementation of the 2012 ICJ Judgment

Though Colombia's government has accepted the authority of the World Court in principle for both the 2012 and 2022 judgments, it's also insisted that it can't actually change its own laws about where its borders lie (including where its EEZ and contiguous zone extend to). Colombia's constitution says the only way to change the country's borders is through a treaty, and the Colombian constitutional court confirmed in a 2014 ruling that the government was correct in interpreting that rule to mean it couldn't fully and immediately comply with the 2012 judgment.

Back to the present, when Colombia's representative says the ICJ's new order to change the contiguous zone law can't be implemented without a "special procedure", he's presumably talking about that same constitutional hangup. Based on Colombian law, the "procedure" to implement the court order would apparently have to be either a new treaty (for example, one signed with Nicaragua) or an amendment to the constitution. So in reality, though Colombia's government doesn't dispute that the court order is binding, it's hard to say when it might actually implement it.

More PolGeoNow Articles on Sea Border Disputes and ICJ Rulings:

- Somalia v. Kenya: Maps of Maritime Boundary Dispute and 2021 ICJ Judgment

- Costa Rica v. Nicaragua: Map of Land Border Dispute and 2018 ICJ Judgment

- Peru v. Chile: Map of Maritime Boundary Dispute and 2014 ICJ Judgment

- Burkina Faso & Niger: Map of Land Border Dispute and 2013 ICJ Judgment

- Map of the Falkland Islands' Disputed Maritime Zones (Argentina-UK)